Punishing Pushy Women: Gender and Power in the Newsroom

Until last week, Jill Abramson, the executive editor of the New York Times, was considered the nineteenth most powerful woman in the world. She was the first woman ever to hold that particular job, and she managed it during a challenging period, as the Times moved to embrace digital technology and cope with the changing face of American journalism. On Wednesday, May 14, however, the newspaper’s publisher, Arthur O. Sulzberger Jr., announced unexpectedly that he was firing Abramson. He replaced her with Dean Baquet, who thanked Abramson for her work and noted that he was taking over “the only newsroom in the country that is actually better than it was a generation ago.” And just like that, Abramson — who played a major role in making those improvements at the Times — was out of a job.

Sulzberger did not explain why he fired Abramson. If anything, his statement raised more questions than it answered. He noted, for example, that the newspaper’s editorial quality had been “better than ever” under Abramson. He praised her efforts to move the New York Times into the digital world, and he claimed that there was no major conflict between them regarding “the critical principle of an independent newsroom.” The only thing he said about the reason for Abramson’s dismissal was frustratingly vague: “new leadership” he claimed, “will improve some aspects of the management of the newsroom.” Unsurprisingly, this statement — and Sulzberger’s refusal to elaborate or take questions — basically left everyone wondering what had really happened. If Abramson had been presiding over a stellar newspaper that was moving confidently into the future, why was the New York Times dismissing her so abruptly?

According to reports that surfaced immediately after Sulzberger’s announcement, there were a few reasons. First, it seems that Abramson may have been dismissed because she was perceived as “difficult to work with” — stubborn, assertive, and sometimes “brusque to the point of rudeness.” Second, Abramson had recently confronted the paper’s management about pay discrepancies at the New York Times. Apparently, she was being paid significantly less than her male predecessor, Bill Keller, had been, and a male deputy managing editor was being paid more than she had been when she had held that position. Third, Abramson was pressing to hire a deputy managing editor for the digital face of the newspaper, which caused some tensions in the newsroom and complaints from editors — including Dean Baquet, who ultimately got Abramson’s job.

Now, on the surface, that seems like three separate reasons for the New York Times to replace Abramson. But here’s what I think. I think (as others have noted) that those reasons all boil down to one basic factor: Abramson was pushy, aggressive, and stubborn. People thought she was kind of a bitch. And to fire her for those personality traits is sexism, pure and simple. Can you imagine an executive editor of the New York Times succeeding without being pushy? Can you imagine a male executive editor of the New York Times losing his job for stubbornness? For aggression? For making a few waves in the newsroom? For asking questions about his salary?

Nursing Clio’s readers are, I’m sure, well aware of these dynamics. Men who behave in certain ways are ambitious, capable, determined go-getters; women who do the same are pushy, bitchy, and domineering. Where men are praised for independence and judgment, women are scolded for thinking too much of themselves and failing to be good team players. Oh, and also, why aren’t they home making babies? Or pies? Aren’t their ovaries going to shrivel up?

In all seriousness, assumptions about ideal masculine and feminine traits have caused problems for professional women ever since being a professional woman was a thing that could happen. In the middle of the nineteenth century, for example, the first generation of American women physicians struggled to reconcile the prescribed set of desirable feminine traits — delicacy, sensitivity, kindness, and maternal instinct — with the supposedly masculine world of medicine. In fact, as historians such as Regina Morantz-Sanchez have demonstrated, many women doctors managed to succeed only because they argued that certain “womanly” traits, like sympathy, compelled them to learn how to heal the sick. But doing so only got them so far. Once “in the door,” they still had to contend with a professional community and a general public that would not hesitate to chastise them for behaving in an “unladylike” fashion – a challenge faced by women in almost every profession. There’s certainly been tremendous progress for women since the nineteenth century, but the core tensions between perceptions of appropriate professional behavior and perceptions of appropriate feminine behavior persist.

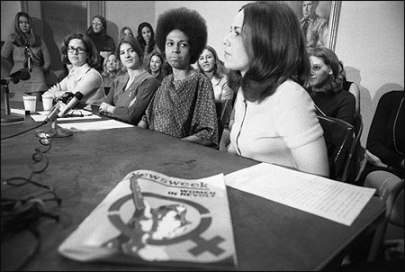

Journalism, it turns out, is no exception to this rule. In 1970, 46 female Newsweek employees, led by Lynn Povich, alleged that the magazine allowed only men to write and report. Educated, qualified female employees were hired only as “researchers” and then kept busy answering telephones and addressing envelopes. With the help of Eleanor Holmes Norton, then a lawyer with the American Civil Liberties Union, the group filed and won the profession’s first sex discrimination lawsuit. In 1975, Povich became the first woman senior editor at Newsweek. She later became the editor-in-chief of Working Woman and then the East Coast Managing Editor of MSNBC.com. Ultimately, she was one of the most successful female journalists of the twentieth century.

And guess what? She had to be pretty damn pushy to do it. Stubborn, even. Aggressive. She had to plan secret meetings with other female journalists, speak to lawyers, file lawsuits, and demand fair treatment. I’m willing to bet that she made some waves in the newsroom.

Jill Abramson graduated from Harvard, earning a B.A. in History, in 1976. She started working for Time the same year — only six years after the Newsweek women filed their sex discrimination lawsuit and one year after Lynn Povich became a senior editor. Surrounded by men, she covered the 1976 election. She took jobs at The American Lawyer and the Wall Street Journal and joined the New York Times in 1997, first as an “enterprise editor,” then as the Washington editor and Washington bureau chief. In 2003, she became Bill Keller’s managing editor, and finally, in 2011, she was named the executive editor. Given the state of the profession and the bias against her as a woman, I find it impossible to imagine that she could have done these things without sometimes being “pushy.”

We may never know all the details behind Abramson’s dismissal from the New York Times, but gender clearly played a role in how she was perceived. What is the lesson here? Women in twenty-first-century America are told, on one hand, that they don’t need feminism — the major battles are won, and they can make their own choices, chart their own paths, and find success by “leaning in.” On the other hand, they are punished for ambitious or aggressive behavior, hated for being “brusque” or pushy, and subject to tremendous amounts of guilt no matter how they resolve the question of “work / life balance.” Women still make less than men make for the same jobs, but the executive editor of the New York Times? She’s supposed to keep her mouth shut about it and play nicely.

As a white, wealthy, Harvard-educated professional in the United States, Abramson obviously has a great deal of privilege. For God’s sake, let’s remember that she was number 19 on the Forbes list of the most powerful women in the world. But she lost her job last week, apparently because her personality traits — traits that were probably necessary to get her into that job in the first place — annoyed people (mostly men). I’m inclined to agree with Ruchika Tulshyan, who, writing for Forbes, argues that what this story reveals is that “even the world’s most powerful women are not safe from negative narrative if they are assertive.” If Abramson wasn’t able to avoid this pitfall, who would be?

The publishers of the New York Times seemed to want a female executive editor who was meeker, more grateful, more willing to compromise. Is that what women in the workplace should be aiming for? Maybe the lesson here is the opposite: that women need to learn to be more demanding, more willing to make waves. Maybe we should all ask our employers if we are making what our male colleagues make and start calling lawyers when the answer — as it so often turns out to be — is “no.” Maybe we should stop thinking of “progress” as a thing that will just happen, inevitably, if we stay committed to whatever work it is we do. They can’t fire all of us, can they?

Further Reading

Regina Markell Morantz-Sanchez, Sympathy and Science: Women Physicians in American Medicine (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985).

Lynn Povich, The Good Girls Revolt: How the Women of Newsweek Sued Their Bosses and Changed the Workplace (New York: PublicAffairs, 2012).

Nan Robertson, The Girls in the Balcony: Women, Men, and the New York Times (New York: Random House, 1992).

Featured image caption: A scene from 1940’s His Girl Friday, starring Rosalind Russell and Cary Grant. (Columbia Pictures)

Carrie Adkins earned her Ph.D. in U.S. History from the University of Oregon in 2013. Her specific scholarly interests include gender, sexuality, race, and medicine in American history.

Discover more from Nursing Clio

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.