“The Sex Lady Talks”: Disability Rights and the Normalization of Sex in a 1980s Institution

When recreational therapist Lisa Freeman began working in the Dual Diagnosis Unit at Indiana’s Central State Hospital in 1986, she frequently encountered patients having sex in and around the unit.1 Central State was a long-term psychiatric hospital and the Dual Diagnosis Unit (DDU) served patients who had been diagnosed with both mental illness and intellectual disability. As Freeman later recalled, on the DDU, “it was not uncommon to hit a stairwell and find people copulating in the stairwells or behind the bushes in the grove or outside your office door.”2 At Central State, as in most 20th-century psychiatric institutions, staff traditionally responded to sexual behavior among patients with punishment or denial. Freeman departed from these norms and instead attempted to create a sex-positive environment where DDU residents could engage in consensual sexual relationships with dignity and privacy.

Freeman’s advocacy on behalf of patients’ rights to sexual intimacy reveals some of the complexities of paternalistic models of care for people with intellectual disabilities in the late 20th century. Grassroots action on the part of DDU staff demonstrates that the expansion of disability rights was possible within state-run psychiatric hospitals during the era of deinstitutionalization. At the same time, it’s important to remember that Freeman’s program was exceptional for its time, and took place within the context of continued limitations on sexual and reproductive rights for people with disabilities in a supposedly post-eugenic era.

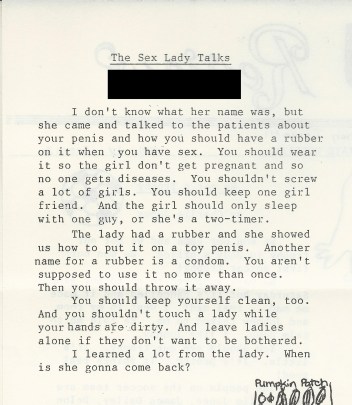

For Freeman, the central issue was consent: “everything was okay if you were an adult and consented to it.” To help create a culture of consent, Freeman brought in an expert. She ignored the hospital hierarchy (in her words, she “went rogue”) and recruited a community educator from the local Planned Parenthood to hold regular classes for residents in the DDU. The educator, known by many residents as the “Sex Lady,” visited the DDU over the course of three months, and used educational videos, dolls, and props to supplement her discussions of anatomy, hygiene, and contraception. The Planned Parenthood educator also advocated for a safe, private place for people to be intimate and ready availability of condoms. With these changes, the problem of patients copulating in stairwells diminished. And as articles in the DDU Review indicated, patients emerged with a greater understanding of safer sex practices and of their own sexual agency, including their right to refuse unwanted sexual advances.

Throughout most of the 20th century, sex between people with disabilities was taboo at best, if not subject to eugenic controls such as forced sterilization and institutionalization. In fact, the state of Indiana passed the world’s first eugenic sterilization law in 1907. Beginning in the 1970s, institutions throughout the United States and Western Europe attempted to “normalize institutional living” for patients with intellectual disabilities or mental illness, for example, by instituting mixed-sex floors. The DDU was established in 1974 in this climate of normalization as an integrated unit at Central State, at the same time that the century-old sex-segregated buildings were demolished. As Allison Carey has argued, the principle of normalization, although it “stressed the pursuit of equality and liberty,…it also legitimated professional supervision and control.”3 At Central State, sexual behavior among residents of a mixed-sex unit proved to be a controversial issue that care staff were left to negotiate.

Our attempts to piece together and frame the “Sex Lady’s” visits to Central State Hospital encapsulate some of the complexity of researching and writing disability history of the recent past. The “Sex Lady” first appeared to us in the pages of the DDU Review, a patient-authored newsletter produced by residents who were members of a “newspaper club” from 1986 through 1993, providing a record of patient life at Central State Hospital in the years before its 1994 closure. The newsletter was an unusual source, in that it appeared to be candid writing by people in the long-term psychiatric hospital who also were classified as having intellectual disabilities.4 While we do not doubt that people with disabilities are reliable narrators of their own lives, we also sought to investigate the process through which the DDU Review was produced. To understand more about the people who lived in the DDU and the context of the newsletter, we turned to oral histories with staff members who worked on and around the DDU.

Our first oral history was a group interview with three rehabilitation therapists, including Lisa Freeman, who started the DDU Review as a therapy program. When we asked about the “Sex Lady,” they made it clear that sex education was, like the establishment of the DDU Review itself, an important touchstone in their work. Freeman and her colleagues argued that adult patients should be able to enjoy the pleasures of consensual sex. They considered the education “revolutionary” because information for intimacy between same-sex partners was provided. Education about consent remained central to the efforts, as Freeman recalled: “You had to consent … nobody could make you do that, whether it was same sex or opposite sex.” Freeman and her colleagues believed patients could be taught to understand the importance of consent and the potential consequences of sexual activity, and that they could freely make decisions for themselves. One of the therapists recalled taking a patient to the public library to get the book The Joy of Sex, and that after looking at the pictures in the book, the patient decided that sex was not something she was interested in.

Not all staff were on board with providing information and support for sexually active patients. Some staff members that we interviewed maintained that people in the unit were incapable of meaningful consent because they had an intellectual disability. As one nurse told us, “if they’re aware enough, or have mental capacity … to have sex, then they don’t need to be a patient here.”5 Perhaps because of the ethical and moral ambiguities, some staff chose to ignore (and later, as we found during some oral history interviews, even deny) sexual activity among patients. That much of the sex between patients was transactional in nature seems to have made many staff members uncomfortable (sex in exchange for cigarettes was particularly common). Sex-positive programs like Freeman’s assumed that sexual activity would occur in the context of romantic relationships, not as forms of sex work. These discomforts reflect broader, unresolved conversations about sex work in general, as well as the rights and capacities of individuals with disabilities and the way sexual relationships were shaped by institutionalization during the 1980s and 1990s.6

The rehabilitation therapists’ focus on patients’ agency and quality of life contrasted with the approach of other Central State staff, particularly physicians and nurses, who regarded patients’ sexual activities as something managed through biomedical means. For them, the central issue was the prevention of reproduction.7 Often in cooperation with patients’ families, physicians and nurses relied on psychiatric medications that caused infertility, birth control devices like IUDs, and (much more rarely) abortions to limit the consequences of patients’ sexual activity. Such measures were practical responses to the reality of widespread sexual activity—both consensual and non-consensual—at CSH.8 As the former hospital superintendent told us: “I don’t know how you keep it [sex] from happening, if you have one or two people on a ward and all of the rooms are back there with doors maybe open but mostly closed, it’s just almost impossible. So, we just made sure that there were birth control pills properly signed for, and then properly administered.”9 The efforts of Freeman and her colleagues to promote safe and enjoyable sex on the DDU represented a notable departure from the institutional status quo.

While anti-eugenic legislation and federal policy provided the beginnings of a top-down framework for disability rights in the late 20th-century, actually improving the quality of life of people with disabilities often required grassroots action on the ground. For a brief time, therapists at Central State facilitated safer sexual practices, affording patients more dignity through providing access to private spaces and educational materials that would make consent possible. On the one hand, we might read this in the context of the limits of normalization, which “assumed that professionals would play a key role in determining and creating ‘normal’ experiences, such as consumers’ goals, activities, living situations, and relationships, and in providing the training believed to be necessary for people with mental retardation to engage in these ‘normal’ experiences.”10 On the other hand, the work of Freeman and her colleagues underscores the important roles care staff, such as therapists, could play as disability advocates, even in an institutional setting.

Central State Hospital closed in 1994, and patients with intellectual disabilities were transferred to group homes and other state facilities. As Carey notes, speaking broadly about the move to community-based settings during deinstitutionalization, Americans with disabilities still found themselves in spaces that “dictated individuals’ access to interpersonal relationships, determined their schedules, and limited their choices and privacy.”11 To this day, services that provide sex-positive education for people with intellectual disabilities are extremely rare. In this light, the “Sex Lady’s” provision of education at a state hospital in 1980s Indiana might be regarded as ahead of its time.

Notes

- With the exception of the rehabilation therapists who spearheaded the CSH DDU Sex Education Program, who granted permission to be cited by name, the authors maintain the anonymity of other former CSH staff who participated in our Oral History Project. Return to text.

- Oral history interview with rehabilitation therapists Lisa Freeman, Bonnie O’Connor, and Terry Duwe, August 16, 2017. This is the source for all subsequent quotations from Freeman. The recording and transcript of this and all subsequently cited oral history interviews are currently held by the Medical Humanities and Health Studies Program, Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis (IUPUI), but will be deposited at the IUPUI Ruth Lilly Special Collections and Archives. Return to text.

- Allison Carey, On the Margins of Citizenship: Intellectual Disability and Civil Rights in Twentieth-Century America, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2009, 178. Return to text.

- For more on the DDU Review and patient journalism at CSH, see Emily Beckman, Elizabeth Nelson, and Modupe Labode, “Voices from the Newspaper Club: Patient Life at a State Psychiatric Hospital (1988–1992).”

Journal of Medical Humanities (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-020-09617-7. Return to text. - Oral history interview with DDU nurse, June 26, 2018. Return to text.

- Winiviere Sy, “The Right of Institutionalized Disabled Patients to Engage in Consensual Sexual Activity” Whittier Law Review 23, no. 545 (2001): 545–577. Return to text.

- Interestingly, none of our narrators mentioned HIV/AIDS prevention as a concern during this time, an issue that we will analyze in greater detail in our monograph. Return to text.

- We have evidence of one patient-on-patient sexual assault that resulted in a pregnancy and an abortion, sanctioned by the patient’s physician and the hospital superintendent, and several other examples of sexual abuse perpetrated by both patients and staff. Return to text.

- Oral history interview with former CSH superintendent, December 17, 2018. Return to text.

- Carey, On the Margins of Citizenship, 178. Return to text.

- Carey, On the Margins of Citizenship, 179. Return to text.

Featured image caption: For a brief time, therapists at Central State facilitated safer sexual practices, affording patients more dignity through providing access to private spaces and educational materials that would make consent possible. (Courtesy PX Here)

Discover more from Nursing Clio

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.