Why the First Woman Matters: Traversing Barriers in the Archives

What started as a straightforward reference question at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) provoked an unmistakable volley in the culture wars – and as I fled from the battlefield via the Archives shuttle, the first woman appointed as Archivist of the United States (AOTUS) saved the day.

The first full week of summer break from my full-time job as a classroom teacher, I headed to the NARA facility in College Park, Maryland, for some long-awaited research for my forthcoming book, tentatively titled Dear Miss Perkins: A Story of Frances Perkins’s Efforts to Aid Refugees from Nazi Germany.

Frances Perkins (1880–1965) was the first female Cabinet Secretary and longest-serving Secretary of Labor in US history. Many people know her as a key architect of the New Deal. My book project adds a new dimension to her story: Perkins enabled the immigration of thousands of refugees from Nazi Germany when the Immigration Naturalization Service (INS) was in the Labor Department from 1933 to 1940.

“Dear Miss Perkins,” wrote countless individuals on the topic of refugee policy between 1938 and 1940. These letters fill boxes at NARA College Park. I spent two days revisiting these incredible sources and finished them on the third morning. Since I was still looking for how the Children’s Bureau fit into children’s refugee policy, I turned next to the Children’s Bureau boxes. A yellow slip redirected me to “Immigration – Refugees.”

After finishing with more boxes of documents, I happily scampered upstairs to Reference to ask what I thought was a straightforward question: Where was this file on immigration and refugees? The Children’s Bureau pointed me to Immigration – Refugees, but I had just finished looking through Immigration, and there was nothing labeled Immigration – Refugees within the Frances Perkins subject files. This should have been a routine question for an archivist, who are generally super helpful and have ample knowledge about materials.

At Civilian Reference, I was directed to a NARA staff member named Tom, who performed a few searches but also told me that I should not try the related record groups, State Department and Children’s Bureau – which I’d suggested from secondary research – because they might take too long to examine. I found this disconcerting, as research inherently takes a long time.

I tried to explain my project, thinking some context might help, but Tom didn’t know who Perkins was, making discussing relevant content challenging. Throughout the conversation, he repeatedly used he/him pronouns for Perkins, even though I kept using she/her. An older woman, likely another researcher, sat down next to us, so I used the entrance of a third party as an opportunity to clarify: “Frances Perkins was a woman.”

This information didn’t seem to faze Tom, who replied, “My great-grandfather was named Francis.” We continued this relatively unproductive conversation, during which he continued to discuss Perkins as if she were male. I was confused and getting increasingly irritated.

I repeated, “Frances Perkins was a woman. She’s she/her.”

The other woman chuckled, “Oh, Tom.”

Tom, still clearly unfazed, retorted, “I don’t care.”

Empowered by having a witness – in the sense that at least I wasn’t imagining that something was off here – I pressed further. Maybe he just didn’t understand what I was trying to research. “Frances Perkins was the first female Cabinet Secretary. Isn’t that interesting?”

Tom doubled down. Perkins’s gender was, apparently, “not important.”

But he wasn’t done. He babbled that he was “happy for her mother” and mumbled something about an alien and a baseball, though at this point he was throwing around more words than I retained. I wasn’t sure what was happening. All I needed was the correct file folder.

Then Tom commented, “Maybe she was gender-confused.” This is when I really became uncomfortable – that last statement signaled to me that he was taking out his bigoted position in the culture wars on my research.

My confusion and irritation coalesced into a conviction that this conversation had become ridiculous. Perkins was a hugely important historical figure as a woman. Tom interpreted my use of “she/her” as “trans person” rather than accepting that women are capable of important positions in US government and history.

If this interaction was difficult for me, a cisgender woman, what would it have been like for a trans researcher, or someone researching trans history? Tom’s response to being corrected on Perkins’s pronouns suggested a complicated overlap of transphobia, misogyny, and a broader bigotry.

After all that, no one was willing to point me toward the “Immigration – Refugees” files I was seeking. I had repeatedly tried to communicate with Tom that they were not in the boxes I’d already viewed, and that all I needed were fresh ideas for where to look. But ultimately, I was left empty handed, and my research was hampered.

Throughout this conversation, I never mentioned that I have a PhD and a book deal, or that I was a finalist for the National Archives’ 2022 Cokie Roberts Fellowship for Women’s History. After all, Reference should take all researchers seriously, regardless of accolades, degrees, or status. But I was certain that when Tom looked at me, he saw no possibility that I was doing something important or interesting. And I’m not alone among researchers with any marginalized status – as others soon made clear on Twitter.

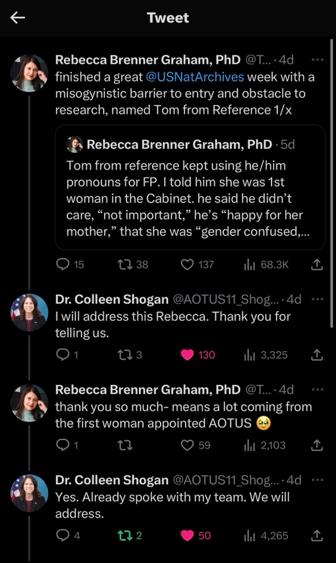

I summed up the frustrating conversation in a tweet and continued to my locker, planning to leave the facility. I realized that it was 2:05 p.m., meaning that I had just missed the 2:00 p.m. shuttle. So I did what any frustrated historian with a Twitter might do: I settled in at the café and continued sharing this story with a Twitter thread.

I concluded with a call to action. I tweeted that although I expected prejudice toward me as a young woman, I was surprised by the indignant refusal of Tom from Reference to acknowledge that Perkins was, regardless of what he wanted to believe, a woman who used she/her pronouns. I hoped that the US National Archives – and I tagged them – could work toward gender equity and accessibility of records, especially under the first woman AOTUS.

My tweets quickly gained traction. Historians on Twitter recognized and related to several aspects. They shared their own frustrating archival experiences, conveyed their interest in Perkins, and expressed solidarity.

This was when the thread moved from commiseration to action. Dr. Colleen Shogan, the Archivist of the United States, replied to me directly: “I will address this, Rebecca. Thank you for telling us.”

I took the next shuttle to DC, then took the Metro to Tenleytown. By the time I got to American University, I received a phone call from the chief operating officer (COO) of the National Archives. We had a reassuring conversation. He grasped the nuances and the severity of what occurred, and he also understood what I really wanted: to blow open barriers to entry, overcome obstacles to research, and simply find an answer to my research question. The next day, I received supportive follow-up emails from the COO, the head of Research Services, and a supervisory archivist. I’m grateful to all of them. As my husband observed, I was taken seriously by people in power, which gave me hope that this experience might bring positive change for other researchers.

The National Archives is one of my favorite research institutions. While this incident wasn’t my first experience with disregard and misogyny in the Research Room – and historians on Twitter shared a seemingly endless slew of similar examples – this was the first time that I received such an effective response. The positive change, I believe, came from the first female AOTUS because, as a fellow woman scholar, she personally understands the experience that I had.

As a friend pointed out on Twitter: “If this was the reception you – a white, feminine, straight woman – got from him, imagine how he’d treat someone like me.” She identifies as queer and doesn’t present as white. “There’s no way his mistreatment of you today was without precedent,” she added, and she’s right. Imagine if a researcher corrected Tom on their own pronouns rather than a historical figure, a safe distance away in time.

Tom from Reference misunderstood why the first woman in a position matters. To some people, the fact that Perkins was the first woman Cabinet Secretary or that Dr. Shogan is the first woman appointed AOTUS remains underappreciated. But that made Shogan’s response extra powerful to me. By now, I trust that Tom has begun learning that the first woman to hold a powerful office exerts a measurable effect.

Being the only woman in the room was a formative part of Perkins’s experience. Critics of her immigration policy sent her hate mail with misogynistic slurs and threats. She navigated gender politics every day, from how she spoke to what she wore: a signature tri-cornered hat that signaled respectable femininity. Perkins advocated for women in many cases, such as working on the issue of material mortality because she herself almost died in childbirth.

Shogan didn’t need to act on a junior scholar’s Twitter thread. She undoubtedly has bigger fish to fry. But she did respond, and then followed through on her promise, because she likely has firsthand experience of not matching a common preconceived notion of “scholar.” She understands that who has research access is important, and that people of all backgrounds and all marginalized statuses must have equitable access to the records of the US federal government. Who has access to archives affects whose stories are told and who gets to tell them.

This day at the National Archives at College Park turned out to be more eventful than I anticipated. But thanks to Dr. Shogan, what could have been a terrible day ultimately made me proud to be a woman historian, prouder than ever to be researching women’s history, and thrilled to be conducting that research at the US National Archives.

Featured image caption: Frances Perkins ( Courtesy Library of Congress)

Rebecca Brenner Graham is author of Dear Miss Perkins: A Story of Frances Perkins’s Efforts to Aid Refugees from Nazi Germany, forthcoming from Kensington in February 2025. She is a History Teacher at the Madeira School and an Adjunct Professorial Lecturer at American University. She holds a PhD in History from American University.

Discover more from Nursing Clio

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

1 thought on “Why the First Woman Matters: Traversing Barriers in the Archives”

Comments are closed.

Thank you. Reading your account, I kept wanting to believe that your experience was something out of the Twilight Zone, but was increasingly disheartened. Not giving in to the oppressive pull, your “speaking out” gives an example for all to follow.