Imagining Sex Change in Early Modern Europe

Once a historical mind starts thinking about the ways sex intersects with the histories of medicine, it’s almost more difficult to divorce the two. Sex itself is physiological, psychological, and, historically, subject to a range of medical scrutiny. The histories of some particular realms of medicine are equally and obviously inextricable from sex – from eugenics to reproductive health – but there are certainly connections to be made in more unsuspecting corners of #histmed. Today we are pleased to open a more regular series of stories that will engage the rich and diverse convergence of sexuality and medicine histories, in which our authors explore eugenics, early modern European sex changes, wife murder, and more.

President Trump recently announced a ban on transgender military personnel, the latest salvo in what has been described as “a new gender revolution.”1 This revolution is an ongoing contest on multiple fronts: legal and medical, political and popular. Arguing against the notion that sexual dimorphism is essential to ideal good health, there is emerging consensus among medical scientists that children born with ambiguous genitalia should not be subjected to aesthetic, gender-affirming surgeries.2

Advocating for the cultural corollary of this science, former pop-cultural icons of masculinity and femininity Caitlyn Jenner and Miley Cyrus publicly rejected these gendered stereotypes, declaring themselves transgender and gender-fluid, respectively.3 But opposing this movement to overthrow binary sex-gender norms are the military ban and “bathroom bills,” regulating restroom access along strict male/female lines, denying people whose identities are in any way non-binary of spaces in which to be themselves.

From the revolutionary rhetoric, one might think that we are witnessing a novel degree of sex-gender confusion and redefinition, but Michel de Montaigne, the sixteenth-century French philosopher, would disagree. In 1580, he wrote in an essay “On the Force of the Imagination” of Marie Garnier, who was female up until age 22, when she suddenly changed into a male.4 This change of sex was publicly acknowledged, and once rebaptized he lived to old age as a man named Germain.5 Garnier’s case, which also featured in royal surgeon Ambroise Pare’s book On Monsters and Marvels (1573), is just one of many examples of sex change and gender redefinition that fascinated readers during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.6

Understanding Sex Difference

Despite intervening centuries of medical progress and the benefit of genetic, biochemical, and neuroimaging technologies, we struggle to understand the mechanisms of sex difference and gender identity.7 How did Pare, Montaigne, and their readers make sense of sex-change stories like Garnier’s?

Early modern medical professionals and laypeople understood human bodies according to the principles of Humorism. Bodies were composed of four humors (blood, phlegm, yellow and black bile) with corresponding elements (air, water, fire, and earth) and associated qualities (hot, cold, dry, and wet.) The perfection of the male body was justified by its hot, dry constitution, which was a product of its external genitalia.

In contrast, the female body was an imperfect version of the male, with a cold, damp constitution and genitalia nestled inside the body. Insofar as the male/female gender binary was explained by constitution and the resulting inversion of otherwise homologous genitalia, this difference was fungible, changeable with the humoral weather.8

Thus, Pare explained how Marie Garnier, after warming herself by “rather robustly chasing swine” and jumping over a ditch, found “the genitalia and the male rod come to be developed in him, having ruptured the ligaments by which previously they had been held enclosed.” According to Montaigne, Garnier himself embraced this explanation, attributing his change to “straining himself in a leap, [so that] his male organs came out.” Subsequent examination by physicians and surgeons confirmed “that she was a man,” and when Pare met Garnier it was as a shepherd named Germain, “a young man of average size, stocky, and very well put together, wearing a red, rather thick beard.”9

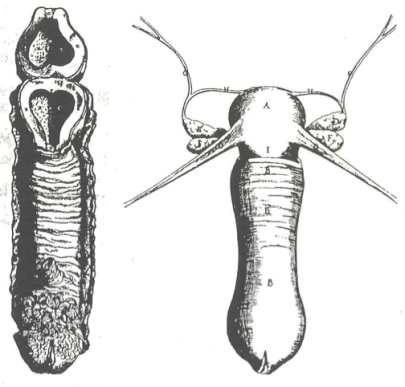

“The vagina and uterus,” from Vidus Vidius, De anatome corporis humani, 1611. (Source: Thomas Laqueur’s Making Sex, p. 82.)

Motivating Sex Change

With all sexed bodies resting on a single humoral spectrum, their locations variable in response to exercise, diet, and other medical interventions, everyone had the potential to change sex. No wonder, then, that Montaigne discovered girls singing a song “in which they warn each other not to take great strides lest they become boys, ‘like Marie-Germain’.” But Montaigne proposed a different mechanism, arguing that “in girls [the imagination] dwells so constantly and forcefully on sex that it can…easily make that male organ a part of their bodies.” The change from female to male was primarily motivated by psychology, rather than physiology, with the persistent female desire for a penis conjuring one into being.4

It is unclear whether Montaigne meant that these changed girls wished to be penetrated by a penis, or to possess a penis with which to penetrate one another, an ambiguity maintained by his report that Garnier “remained unmarried.” Garnier made no public declaration of his own sexual orientation or any claim on the sexuality — and by extension the property, progeny, or power — of another.

Early modern society was patriarchal, its basic political unit a household headed by a husband and father, who was considered naturally suited to rule over his dependents by virtue of his physical perfection. An unambiguous change from Marie to Germain, from female to male, did not violate these established gender roles, but rather reinforced them, by exemplifying how “Nature tends always toward what is most perfect” in its pursuit of male sex.7

Negotiating Sexual Orientation

Despite his acknowledged masculinity, given public memory of his former female identity, Garnier was probably wise not to push his luck by marrying and claiming the valuable social and cultural prerogatives of patriarchy. The concept of the natural perfection and rightful dominion of the male sex was too important and too tenuous to withstand any taint of sexual ambiguity. Garnier’s situation is reflected in the choice made by many transgender people today, to assume prudishness out of prudence and “only talk about their genders and never their sexualities,” in order to gain safety and “acceptance from a sexually conservative majority.”10

Exemplifying the need for this caution is the case of another former Marie, who in 1601 was jailed and sentenced to death after she changed sex, took on the masculine name “Marin,” and announced an intention to marry the widow Jeanne le Febvre.11 Ultimately, Marie-turned-Marin de Marcis was spared the death penalty, thanks to the surgeon Jacques Duval who testified to his masculinity, in opposition to several other medical authorities, including the celebrated physician and anatomist Jean Riolan. Duval’s digital examination of the apparent vagina revealed a buried phallus, which was stimulated to erection and ejaculation, meeting the medicolegal criteria for a male penis.

Authorizing Sexual Identity

When asked why De Marcis’ captors never saw his penis, Duval offered a traditional humoral explanation: that the circumstances of imprisonment — the absence of good food, fresh air, exercise, and the company of the beautiful Jeanne — rendered his complexion chill, damp, and effeminate. But Duval’s argument was founded on a more radical epistemic claim: that clinical examinations by the surgeon’s hands were more reliable sources of medical information than the traditional academic training that gave physicians like Riolan their authority. Whereas Riolan claimed anatomical expertise by viewing the body, in privileging the sense of touch over sight Duval not only claimed expert knowledge and authority for surgeons over physicians, but also an understanding of the invisible secrets of the (purported) female body, formerly only the purview of midwives.12

Duval’s claim to specialist knowledge for surgeons was but one sally in an ongoing culture war within the profession, over the basis of medical authority. In the previous century, the Paris faculty of medicine sued Ambroise Pare for writing on matters beyond the scope of a mere surgeon, and of compounding this error by writing in vernacular French, rather than scholarly Latin. This made Pare’s knowledge accessible to laypersons, a democratic attitude reflected in his management of genital ambiguity. Pare felt that “expert and well-informed physicians and surgeons can recognize whether hermaphrodites are more apt at performing with and using one set of organs than another, or both, or none at all,” but ultimately left assignment of sex and gender identity up to the person in question.13

Considering Sex Change: From Past to Present

During the centuries that followed, the medical profession gained further specialist authority, in part by depriving patients of their own claims to self-knowledge, a process that sociologist Nicholas Jewson termed “The Disappearance of the Sick Man.”14 By the eighteenth century, when the English surgeon Thomas Brand identified a 7-year-old boy who had been baptized as a girl and operated to enable the child “to urinate standing up, wear trousers, and enjoy the privileges of being a male,” he explicitly deemed the feelings of the child and parents irrelevant. This was particularly true as the genital anomaly in question was identified at a Dispensary for the Poor, and therefore, like Garnier before, made no claim to significant property or power. Brand concluded that in a different social context, “if the same kind of malformation should ever happen in a child of rank, it might prove an interesting and important case.”15

A recent article in Nature considered a similar case, but with a very different result: describing how twenty-first-century science supports a non-binary concept of sex and gender, it concluded like Pare: “if you want to know whether someone is male or female, it may be best just to ask.”16

This embrace of patient autonomy and self-expression, touchstones of the “gender revolution,” heralds a “reappearance of the sick man” — terminology that is troublingly apt, as medical research and practice continue to privilege cis-gendered men, while neglecting the needs of other-gendered populations. Just as the boundary-pushing works of Pare, Montaigne, and Duval ultimately reinforced the norms of the patriarchal society in which they lived, without diligent advocacy work, today’s progressive science is also at risk of being subsumed by reactionary politics.

Notes

- Diane Ehrensaft, quoted by Jon Brooks, in “Boy? Girl? Both? Neither? A New Generation Overthrows Gender,” KQED Future of You, April 24, 2017. Return to text.

- M. Jocelyn Elders, David Satcher, and Richard Carmona, “Re-thinking Genital Surgeries on Intersex Infants [PDF],” Palm Center: Blueprints for Sound Public Policy (June 2017). Return to text.

- For rhetorical purposes, I use “sex” when referring to biology and eroticism, and “gender” when referring to culture and identity, even though a strict separation between these is notoriously difficult to justify, as argued by Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1990). This was particularly true in the early modern context, with “sex” and “gender” lumped together as a “natural,” as opposed to “unnatural” state of being: see Lorraine Daston and Katherine Park, “The Hermaphrodite and the Orders of Nature: Sexual Ambiguity in Early Modern France,” GLQ, 1 (1995): 419-438. Return to text.

- Pronouns are chosen to reflect the actor’s own lived expression of his/her identity; hence: “her” when living as Marie and “him” when living as Germain. Return to text.

- Michel de Montaigne, “On the Force of Imagination,” in The Complete Essays (Penguin Classics, 1993). Return to text.

- Although the evidence that follows comes largely from France, it exemplifies early modern medicine throughout Europe and Britain. Return to text.

- Claire Ainsworth, “Sex Redefined,” Nature 518 (February 18, 2015): 288-91. Return to text.

- Thomas Laqueur, Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990). Return to text.

- Ambroise Pare, On Monsters and Marvels, trans. by Janis L. Pallister (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1982), 31-33. Return to text.

- Brian D. Earp, “In Praise of Ambivalence — ‘Young’ Feminism, Gender Identity, and Free Speech,” Quillette (July 2, 2016). Return to text.

- Lorraine Daston and Katherine Park, “The Hermaphrodite and the Orders of Nature: Sexual Ambiguity in Early Modern France,” GLQ 1 (1995): 419-438. Return to text.

- Katherine Park, Secrets of Women: Gender, Generation, and the Origins of Human Dissection (Brooklyn, NY: Zone Books, 2006). Return to text.

- Pare, On Monsters and Marvels, 26-30. Return to text.

- ND Jewson, “The Disappearance of the Sick Man from Medical Cosmology, 1770-1870,” Sociology 10, no. 2 (1976): 225-44. Return to text.

- Thomas Brand, The Case of a Boy Who Had Been Mistaken for a Girl: With Three Anatomical Views of the Parts, Before and After the Operation and Cure (London: Printed for the Author, and sold by G. Nichol, J. Murray, and J. Bew, 1787). Return to text.

- Claire Ainsworth, “Sex Redefined [PDF],” Nature, 518 (February 18, 2015): 288-91. Return to text.

Barbara Chubak is a urologist, specializing in the treatment of sexual dysfunction for all persons, regardless of sex, gender, or orientation. In addition to her MD degree, she has Master's degrees in the history of medicine and bioethics, and applies this scholarship to her clinical practice, research, and teaching. She is currently working on a comparison of sexual dysfunction treatment in traditional Chinese and western biomedicine.

Discover more from Nursing Clio

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.