“For Poor or Rich”: Handywomen and Traditional Birth in Ireland

On Achill Island, Ireland, an untrained woman was prosecuted for acting as a midwife in 1932. In her defense, she argued that she intervened only in an emergency “to save the mother and child.” Here, local authorities decided “not to press the case hard and to ask for a light penalty.”1 Controversies like this were common in the early twentieth century, when tensions between traditional health care workers and the growing medical profession abounded.

These conflicts, of course, have deep historical precedents — struggles featuring “man-midwives” and female midwives dominated reproductive health care in the 17th and 18th centuries.2 The victor in these historical struggles seems clear: most historians have claimed that traditionally trained female healers and birth attendants were completely overtaken by newly educated physicians in the modern era.

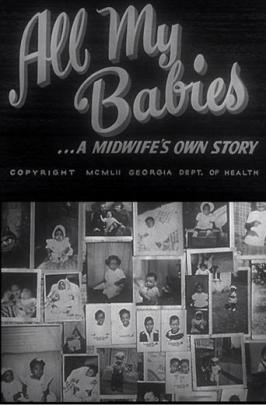

Tradition does not die so easily, however. We now know that in the American South, African-American midwives like Georgia’s Mary Coley (featured in the documentary film All My Babies) worked through much of the twentieth century. More recently, the success of Ricki Lake’s documentary films and the small but near-cult following of Ina May Gaskin in the United States have led to a resurgence of home births and a rejection, by some, of the medical model.

Parts of Europe, and particularly rural areas, have witnessed similar historical continuities. Ireland, an overwhelmingly rural and agricultural country until very recently, serves as an ideal case study for examining the persistence of custom and women’s communities in the modern world. In Ireland, births traditionally were attended by handywomen. These women — commonly informally trained female family members or neighbors — are hard for historians to trace. They rarely interacted with officials or the written word. Their world was one of orality and sometimes secrecy. Recent research in Irish folklore collections has demonstrated, however, that they were the primary reproductive health care givers through the early decades of the twentieth century in some areas.3

And their knowledge and authority did come under attack as Ireland modernized. By the latter decades of the nineteenth century, newly trained nurses and midwives made their way across the Irish landscape. The Queen Victoria Jubilee Institute for District Nursing began to train nurses in Ireland in 1891; the Lady Dudley scheme followed shortly thereafter, in 1903. In 1904 a Catholic priest described the need for these professional women:

[gblockquote]“[T]he poor people of this district are severely tried, inasmuch as there is no District Nurse and no doctor within a distance of six Irish miles …. I have laboured amongst them during the past five years, and the deaths in cases of maternity have been many. The people are the poorest of the poor, and being unable to pay a doctor’s fee, which would be heavy owing to the great distance, they trust to chance. The consequence is that many young mothers die whose lives would be saved, given the proper assistance was at hand. During the past year, not to go back, I came across no less than five cases where the mother died simply because the proper trained assistance was not present.”4[/gblockquote]

As observers called for medical professionalization in Ireland, and specifically for trained nurses and midwives suitable for maternity care, they produced a plethora of rhetoric claiming that the existing care offered by handywomen was dangerous. In fact, handywomen became criminalized in the early twentieth century, and complaints against them increased. One trained nurse wrote in 1912:

[gblockquote]“Called to this patient after birth of child. Handy woman was in charge. The handy woman got drunk and forgot about patient and child. Patient sent for doctor, also asked doctor to send for nurse. Patient was very grateful for my attention. Said she would have had nurse from beginning only for neighbouring women who declared handy woman was lucky.”5[/gblockquote]

These impressions that handywomen were dangerous, untrained, and unsanitary, however, were not shared by all the people they served. Impressions given by ordinary Irish folks affirm that handywomen were good at their jobs and did what they could to help pregnant and laboring women. Several oral history accounts collected by historian Caitriona Clear reveal admiration for handywomen. One man, discussing life in early twentieth-century Sligo, remembered “… they [handywomen] were very old at that time and I think they loved the job. There was always entertainment on an occasion such as that and it wasn’t weak tea but they done their job if it was water they got, for poor or rich.”6

Sometimes, handywomen were the only available option for women in need of reproductive care. Handywomen, then, persisted. And in rural areas, birth continued to take place in women’s homes, usually with a female (nurse, midwife, or handywoman) attendant. In some ways, therefore, childbirth remained female-centric and tied to the home well into the twentieth century, particularly in isolated, rural areas. This was not a phenomenon unique to the US or Europe either; Glenda Strachan has discovered that in late nineteenth-century Australia, about half of rural women were delivered by handywomen, and the other half by relatives and/or neighbors, without money being exchanged.7

While gaining access to the words and thoughts of traditional healers, including handywomen, remains difficult, they have much to say, and we should try to recover their stories. An understanding of the ways in which handywomen influenced reproductive care and childbirth practices in Ireland helps us understand women’s daily lives in the past. These stories also provide much-needed context for those issues and debates, including abortion in Ireland, that continue to grab our interest.

Notes

- Mayo News, August 27, 1932. Return to text.

- See Adrian Wilson, The Making of Man-Midwifery: Childbirth in England, 1660-1770 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995). Return to text.

- Ciara Breathnach, “Handywomen and Birthing in Rural Ireland, 1851-1955,” Gender and History 28:1 (April 2016): 46. Return to text.

- Lady Dudley’s Scheme for the Establishment of District Nurses in the Poorest Parts of Ireland, Second Annual Report, 1904, 14. Return to text.

- Lady Dudley’s Scheme for the Establishment of District Nurses in the Poorest Parts of Ireland. Tenth Annual Report, 1912, 15. Return to text.

- Caitriona Clear, Women of the House: Women’s Household Work in Ireland, 1922-1961 (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2000), 102. Return to text.

- Glenda Strachan, “Present at the Birth: Midwives, ‘Handywomen’ and Neighbours in Rural New South Wales, 1850-1900,” Labour History, No. 81 (Nov., 2001): 13. Return to text.

Cara Delay, Associate Professor of History at the College of Charleston, holds degrees from Boston College and Brandeis University. Her research analyzes women, gender, and culture in nineteenth- and twentieth-century Ireland, Britain, and the British Empire, with a particular focus on the history of reproduction, pregnancy, and childbirth. She has published in The Journal of British Studies, Lilith: A Feminist History Journal, Feminist Studies, Études Irlandaises, New Hibernia Review, and Éire-Ireland and written blogs for Nursing Clio and broadsheet.ie. Her co-edited volume Women, Reform, and Resistance in Ireland, 1850-1950, was published with Palgrave Macmillan in 2015, and her monograph on Irish women and the creation of modern Catholicism is forthcoming from Manchester University Press. At the College of Charleston, she teaches courses on women’s history and the history of birth and bodies.

Discover more from Nursing Clio

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.