Surviving While Black in America: A Review of Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me

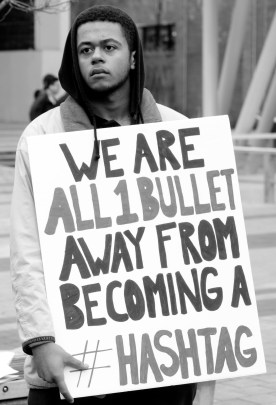

One of the products of Americans’ growing consciousness around racism and the police killings of African Americans is the conversation about the “talk” that African American parents conduct with their sons and daughters. I do not recall my mother and father engaging me in a specific conversation, but rather a series of conversations about navigating everyday racism, interacting with police, and dealing with the criminalization of my body. My mother’s talk with me was gendered. She grounded her lessons in “the killing of our black boys” discourse that has circulated in black communities for decades. My mother often remarked about how young black men constituted an “endangered species.” I learned that discrimination, incarceration, and death hung over my life. Thus, it was important that I studied and worked hard and stayed out of trouble. I never forget about how she often told me that I needed to be careful if I hung around white Americans because I was likely to shoulder the burden of punishment if we ran into trouble.

In Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates invites readers to engage in the conversation that many black parents conduct with their sons and daughters. Coates grounds his lessons to his son, Samori, in his own personal narrative. In doing so, the author addresses many topics — white supremacy, American exceptionalism, the black body, police violence, Afrocentricity and black nationalism, respectability politics, and hip hop culture. Between the World and Me not only functions as a warning to Samori and the youth who look like him, but one to a nation deluded by what Coates calls “the Dream.” This Dream inhibits Americans from understanding the persistence of a pernicious white supremacy.

Critics from both the right and the left have challenged Coates’s understanding of U.S. history and the author’s failure to illustrate black agency and progress. To comprehend Coates’s understanding of racism in the 21st-century United States, one must ultimately grapple with the contradictory historical context in which the author grew up. In Between the World and Me, Coates challenges dominant narratives of racial progress in U.S., and African American, history. In seeing structural racism as a powerful material force constantly threatening the black body, Coates pushes back against the efficacy of respectability politics and conservative explanations for individual success and failure. Between the World and Me resists easy solutions to the race problem. Coates’s text exposes the limits of post-1960s black politics and of integrationist civil rights gains.

For Coates, race, racism, and white supremacy contain discursive and material features. “But race is the child of racism, not the father,” Coates writes. “And in the process of naming ‘the people’ has never been a matter of genealogy and physiognomy so much as one of hierarchy.”1 In the text, white supremacy is not a force that just goes away, but it changes over time. For Coates, the black body bears the burden of bringing race to life. “As for now, it must be said that the process of washing the disparate tribes white … was not achieved through wine tasting and ice cream socials, but rather through the pillaging of life, liberty, labor, and land; through the flaying of backs, the chaining of limbs, the strangling of dissidents; the destruction of families; the rape of mothers; the sale of children ….”2 Coates’s understandings of race, racism, and white supremacy recalls historian Jennifer Morgan’s work on African women slaves in her book, Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery. In her book, Morgan illustrates how slaveowners used African women’s reproductive capacities to not only enrich themselves, but to construct “blackness,” which, in turn, reinforced African women’s “enslavability.”3

Coates’s analysis of white supremacy turns on the concept of the “Dream.” The Dream refers to Americans’ cherished notion of equal opportunity and social mobility. Yet, Coates argues that the Dream is intricately connected to plunder — of black bodies, labor, and Native land. Structural racism and the Dream are intrinsically linked. “I have wanted to escape into the Dream, to fold my country over my head like a blanket. But this was never an option because the Dream rests on our backs, the bedding made from our bodies,” Coates laments.4 The Dream signifies a tautology for many African Americans. The dream is just a dream. Coates’s personal narrative asserts that, even if black Americans achieve individual success, white supremacy and structural racism still threatens their bodies. Coates’s painful account of his friend Prince Jones’s death at the hands of police demonstrates the precarity of black life despite individual and familial success.

Connecting the Dream to white supremacy turns one of America’s central myths on its head. The Dream, in all of its rosy colorblindness, is built on the contradiction of liberty and plunder. The subprime mortgage crisis highlights this contradiction. In fact, the subprime mortgage crisis represented the greatest loss of wealth for African Americans ever. It is widely reported that banks extended subprime mortgages loans at a greater rate than they did for whites. For many African Americans during the 2000s, a subprime mortgage represented plunder masquerading as the Dream. The subprime mortgage crisis laid the foundation for conditions leading to the Baltimore uprising.

Many critics challenge Coates’s understandings of racism and his pessimistic view of black life in America. Writers Cathy Young and David Brooks find problems in Coates’s refusal to contextualize his story within a whiggish narrative of American history. Brooks complains that Coates abandoned the American Dream. Meanwhile, African American Studies scholar Melvin Rogers argues that casting white supremacy as a suffocating omnipresent force in black life leaves little room for the hope needed to resist, confront, and to eventually defeat it. Coates does neglect an exploration of the multitude of black responses to white supremacy. However, the problem with wanting Coates to contextualize his life within a progress narrative, or to tell a more optimistic story, is that one would be asking Coates to construct a narrative that did not align with his Baltimorean reality. These analyses also fail to consider the historical context — an era when black politics was largely defensive and in retreat — in which Coates grew up and came of age.

Coates grew up and matured during a contradictory period of African American, and U.S., history. The federal government violently circumvented and repressed black radical activists and organizations such as the Black Panther Party on the heels of voting rights and fair housing legislation in the mid-to-late 1960s. During the 1970s, African Americans voted in their own mayors of major cities like Detroit, Oakland, and Philadelphia, just as industrial plants closed and moved. The federal government abandoned urban policies that helped the rustbelt in favor of block grants that disproportionately aided the fast growing South and Southwest.

As more African Americans ascended into the middle class, the impoverished “underclass” grew. The “war on crime” that President Lyndon Johnson declared in 1964 slowly morphed into President Ronald Reagan’s war on drugs. This war on drugs, as Michelle Alexander illustrates in The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, helped grow the prison population, structured recidivism into criminal justice, and ushered in the next epoch of American racism. The country’s transition from a largely manufacturing-based economy to one grounded in finance served as a backdrop for the development of an illicit drug-based economy. President Reagan demonized black women in order to justify cutting welfare benefits. Black mayors were left to manage these crises. Young black men and women like Coates were left to their own devices to protect their bodies and survive.

Considering particular elements of post-civil rights African American history, one wonders where Coates would have drawn inspiration to validate a whiggish narrative of racial progress. Coates grew up and matured during a moment when the black political imagination was constrained, and black social movements were dormant. By the 1990s, Jesse Jackson had demobilized the Rainbow Coalition, the only left-leaning black-led social movement in the country. African Americans had fully integrated themselves into the national Democratic Party, even as President Bill Clinton slashed welfare rolls and oversaw crime policy that continued the growth of the U.S. prison population. Black scholars like Cornel West captured Americans’ imagination with his text, Race Matters. But West’s critiques of black nihliism and calls for a “politics of conversion” were less likely to recharge black politics.5 Black cultural nationalism reemerged during the 1980s and 1990s. Minister Louis Farrakhan’s efforts to rally black men in the Million Man March reminded African Americans of the limits of politics inspired by the Nation of Islam. Hundreds of black intellectuals and activists tried to revive radical politics during the late 1990s by establishing the Black Radical Congress, but that effort was short-lived.

Resisting narratives emphasizing the American Dream and black hope and resistance, Coates’s Between the World and Me suggests that black survival emerges as the crucial theme of his era. Amiri Baraka asked in 1965, “Who is Going to Survive in America?” Gil Scott Heron echoed the same question in 1970. Kanye West sampled Heron’s song in 2012. The notion of surviving white supremacy is a longstanding motif of black life. In this context, it is not a surprise that Coates disavows hope and optimism. It is not a coincidence that Coates included the Queens-based hip hop group, Mobb Deep, alongside Shakespeare and Fitzgerald in his list of influences.6 As Coates tweeted on July 29, “Hope” was “not a real concern” for the rap group. One only needs to listen to Mobb Deep’s 1995 album, The Infamous, especially “Survival of the Fittest” to understand Coates’s, and other young blacks,’ desires to survive.

Wishes for Coates to offer some words of hope and/or a path toward racial salvation seem logical considering the power that narratives valorizing black resistance, racial progress, and American exceptionalism hold over many Americans’ consciousness. Yet, Coates reminds readers that living while black in America is a grind on the black body. He fundamentally challenges Dr. Martin Luther King’s observation that the “line of progress is never straight.”7 For Coates, the line of progress, itself, may be an illusion. Perhaps it is only a part of the Dream.

Further Reading

Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: New Press, 2010.

Bennett, Brit. “Ta-Nehisi Coates and a Generation Waking Up,” The New Yorker, July 25, 2015.

Lang, Clarence, Black America in the Shadow of the Sixties: Notes on the Civil Rights Movement, Neoliberalism, and Politics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2015.

Marable, Manning. Race, Reform, and Rebellion: The Second Reconstruction and Beyond in Black America. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2007.

Morgan, Jennifer L. Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004.

Mount, Guy Emerson, “Ta-Nehisi Coates, David Brooks, and the Master Narrative of American History,” African American Intellectual History Society, July 25, 2015.

Notes

- Ta-Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me (New York: Spiegel & Grau), 7. Return to text.

- Coates, Between the World and Me, 8. Return to text.

- Jennifer Morgan, Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 1. Return to text.

- Coates, Between the World and Me, 11. Return to text.

- Cornel West, Race Matters (New York: Vintage Books, 1994), 28-29. Return to text.

- Coates does not specify which Fitzgerald in the tweet. Return to text.

- James M. Washington, ed., A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr. (San Francisco: HarperSan Francisco), 562. Return to text.

Austin C. McCoy is a Phd Candidate in History at the University of Michigan. He is writing a dissertation on progressives' responses to plant closings and urban fiscal crises in the Midwest during the 1970s and 1980s.

1 thought on “Surviving While Black in America: A Review of Ta-Nehisi Coates’s <em>Between the World and Me</em>”

Comments are closed.

great review. particularly liked your dissection of the “Dream” as nightmare for non-white America. so looking forward to reading this book.