Justice and Agency: Why Women Love True Crime

When I was young, I was obsessed with Unsolved Mysteries. While not typically a “go-to” show for an eight-year-old, my love of the program was unsurprising to my parents. I voraciously read every single Nancy Drew novel, regularly solved Encyclopedia Brown mysteries, and loved watching Father Dowling Mysteries and PBS’s Mystery! with my grandmother. But there was something different about Unsolved Mysteries: it was true.

Or, at least, eight-year-old me believed it to be true. While perhaps I too readily accepted tales of alien abductions and hauntings, I was particularly drawn to the disappearances and other crimes. Luckily, I had a partner-in-true-crime—my sister—who first introduced me to Vincent Bugliosi’s award-winning book on the Manson murders, Helter Skelter. From there, my love of true crime only grew. If there is a true crime podcast, a documentary film, or series on a streaming platform, I’ve most likely seen or heard it.

I’m not alone in my love of true crime. Especially since the wild success of the 2014 podcast Serial (it became the fastest podcast to ever reach 5 million downloads on iTunes), articles abound on true crime and its consumers. It’s clear the genre is wildly popular. But who is the primary audience? Journalists are fascinated by the fact that most true crime viewers are women, particularly white, middle-class, cisgender women. One study found that out of the twelve most popular true crime podcasts, men listened in larger numbers to only one podcast (Last Podcast on the Left, which is, not coincidentally, hosted by men). Another study found that 80% of true crime enthusiasts were women. This is particularly interesting when one considers the crimes depicted in the genre. Most true crime focuses on female victims and male perpetrators. Why do women seem to enjoy tales of people of their gender being brutalized and murdered?

Think pieces on this question abound online. Some, like one by psychologist Michael Mantell, suggest it’s part of the human condition, arguing “we have been fascinated with the conflict between good and evil since the beginning of time.” Author Lindy West, in a discussion of her love of Law and Order: SVU, suggests two possibilities for her own obsession with true crime. It’s “like pressing on a bruise.” It might be “an effort to normalize this thing that scares me—to eat it and internalize it and own it.” And, of course, much true crime ends with some semblance of justice, with the “bad people” being “systematically put away over and over again.”

However, this does not fully explain why it is that women are particularly drawn to true crime. Although women are more fearful of falling victim to violence, a fascination with criminals and their behavior is, as Dr. Michael Mantell notes, practically universal. What becomes apparent when one consumes more than a smattering of true crime is that women play a central role not just as victims, but as those seeking—and often finding—justice. Indeed, in media that almost solely focuses on the heroics of men, true crime is one area in which women, especially those not traditionally “seen” by the media, become the heroes of their own stories. Too often, women are cast as victims or as actors lacking any real agency; true crime allows women to acknowledge the real possibility of becoming victims of violent crime while, at the same time, imagining a world in which they are able to gain justice either for themselves or for other female victims.

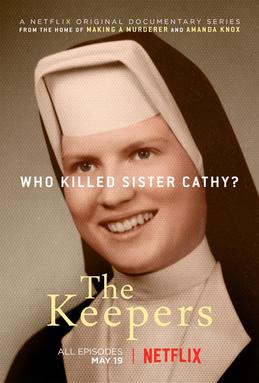

Although not all true crime podcasts and documentaries are made by women or feature female subjects, much of the most popular recent true crime does. From My Favorite Murder, the popular podcast hosted by comedians Georgia Hardstark and Karen Kilgariff, to Netflix’s The Keepers, a docuseries focused on women in their 60s, to I’ll be Gone in the Dark, the bestselling book from journalist Michelle McNamara, true crime creates space for women to seek some form of justice, either for themselves or for others, in a world that consistently denies it to them. Although Hardstark and Kilgariff aren’t aiming to solve any mysteries or bring killers to justice, they do seek to push back against victim blaming in male-dominated media while pointing out the various warning signs our justice system regularly ignores. In a number of episodes, the hosts question both the image of and treatment of female victims, especially in cases involving sexual activity. For example, in episode thirteen, Hardstark and Kilgariff discuss the so-called “Preppy Killer,” Robert Chambers, who murdered Jennifer Levin in 1986. Throughout the case, the media essentially blamed Levin for her own death. As Kilgariff angrily quipped in the episode Thirteen Going on Murdy, “the New York Daily News had headlines like how Jennifer courted death and sex play got rough and her reputation was totally attacked while Chambers was portrayed as a Kennedy-esque preppy altar boy with a promising future.” Although Levin was the victim of a horrific crime, the media at the time suggested her alleged sex diary justified, in some way, her murder at the hands of Chambers. Sadly, this form of victim-blaming is all too common, even in cases of homicide. Although podcasts cannot bring killers to justice, it does rehabilitate the reputation of these women by bringing to light the misogyny present in how we discuss female victims.

Misogyny and the ever-present threat to women is a common thread in true crime told from the perspective of women. In particular, the genre suggests male perpetrators can commit their crimes because of institutionalized misogyny. As Kilgariff notes, “in all of these stories that we tell and cases that we talk about, things happen for a) a reason and b) the people that do them have histories of doing things. It’s so strange that still the legal system treats these things like they’re out of the blue … if a man consistently beats the shit out of his wife, that will escalate.” After reading Michelle McNamara’s expose on the Golden State Killer, one true crime enthusiast remarked, “How a man could rape 50 plus women and kill 10 people and get away with it is basically a primer on institutionalized misogyny.” Exposing the kind of misogyny that allows killers to get away with murder is a form of justice for women who recognize this reality in their own lives.

The kinds of women true crime focuses on in their efforts to seek justice are also unique. Take, for example, Netflix’s docuseries The Keepers. This series examines the murder of Sister Cathy Cesnik in 1969. Gemma Hoskins and Abbie Schaub, two retirees in their 60s who were students in Cesnik’s high school English class, act as the heart of the series, working tirelessly to discover what happened to their favorite teacher and bring her justice. As Schaub remarks in the first episode, “we’re in our 60s. Time is getting short for us to be able to figure out what happened to Cathy. I don’t think there’s any shame in not succeeding, but it would be wrong not to try.”1 As the series unfolds, other women come into focus, Jean Wehner in particular, who suffered sexual abuse as high school students. Tying the abuse to Sister Cathy’s murder, these women act as avenging angels, forcing the Catholic Church to acknowledge the abuse and bringing newfound attention to Sister Cathy’s murder.

Particularly noteworthy about The Keepers is that its focus is almost solely on women over the age of 60. Gendered ageism runs rampant in traditional media. Depictions of women over 40 are relatively rare, and positive images are rarer. However, in The Keepers we follow a variety of women in their 60s, all interesting and complex, all seeking justice for themselves, their community, and Sister Cathy. In My Favorite Murder we listen to two comedians, Hardstark in her late 30s and Kilgariff in her late 40s, who now not only have a wildly popular podcast but also a bestselling book and a sold-out tour. In I’ll Be Gone in the Dark, we follow Michelle McNamara, also in her 40s before she died unexpectedly, obsessively hunt for the truth of the Golden State Killer. In all three, we get to watch, hear, and read about women the media traditionally ignores. And, of course, all three seek some form of justice for female victims of misogyny and male violence.

Women’s presence as heroic actors is chronically lacking in the media. True crime’s popularity among female viewers shows that women crave images of themselves in the media they consume. Perhaps the larger world of media should take notice and centralize the stories of women, showing them as they are: complex, interesting, and heroic.

Notes

- The Keepers. “The Murder.” Episode One. Directed by Ryan White. Netflix. May 19, 2017. Return to text.

Evan is a historian of the 20th century United States who specializes in the history of women’s health activism, particularly among women of color. She is currently working on a project examining coalition building between women of color in the Women’s Health Movement. At Missouri Western State University she teaches courses on American Women's History, Race, Science, and Medicine in American history, African American History, and American History Surveys.