Baby Parts for Sale — Old Tropes Revisited

When Robert Lewis Dear Jr. was finally taken into custody after opening fire on a Colorado Springs, Colorado Planned Parenthood on November 28, 2015 — an attack that killed three people — he allegedly told police, “no more baby parts.” While all the facts about Dear’s motives and actions are yet to be released, on the surface his attack seems connected to the recent debate on fetal tissue sales and Planned Parenthood.

In summer 2015, the conservative Center for Medical Progress (CMP) surreptitiously taped an interview with Planned Parenthood employees in California about the process of recuperating the costs for the (legal) transport of fetal tissue for medical research. The seven videos they have released since — heavily edited to create fictitious situations in which it seemed that Planned Parenthood profited from the sale of fetal tissues (which is prohibited by federal law) — have caused a media maelstrom over the past few months. The president of Planned Parenthood, Cecile Richards, had to testify before a House Committee in a nearly five-hour circus in which (mainly) male legislators engaged in glaring misogyny, interrupting Richards, questioning her salary, and belittling her gender. At one point, Tennessee Republican John Duncan, asked Richards, “Surely you don’t expect us to be easier on you because you’re a woman?” Both the left and the right have been equally outraged about the issue. While reproductive rights organizations have vehemently rejected the videos, conservative activists continue to applaud their truthfulness and have renewed attacks to defund Planned Parenthood.

At the second Republican presidential debate on September 16, Carly Fiorina, the only woman on stage, decided to vocalize her opinion about the Planned Parenthood fetal tissue debate. Fiorina stated, “I dare Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, to watch these tapes. Watch a fully formed fetus on the table, its heart beating, its legs kicking, while someone says we have to keep it alive to harvest its brain. This is about the character of this nation!” Her comments were referring to the CMP’s videos. While Fiorina’s comments have been proven false from people who actually watched the videos, they demonstrate how public leaders and the media will sensationalize the issue of abortion, no matter how falsely, in order to make it illegal.

But no one in the media has seemed to notice that this is not the first time — nor probably the last — that abortion has been connected to the sale of fetal tissue in order to criminalize the practice. As U.S. historians of gender and abortion have argued, in the mid-to-late-nineteenth century, the (male) mass media turned abortion into sensationalist headlines and galvanized popular support against the practice.1 They even accused abortionists of selling aborted fetuses to medical schools for profit.2 For example, in one publication, The National Police Gazette, the editors wrote that the New Jersey abortionist Madame Costello and her husband were selling dead babies: “in relation to these miscreants, some months ago, … they reaped a double harvest from their work of death; and when they slaughtered their victim by their damnable practices, they not only got ‘gold for the murder, but gold for the murdered victim.’” In the same piece, the editors argued that the question at hand pertained to the moral fiber of the American populace, a lá Carly Fiorina: “Is it not a wonder, nay, is it not a neglect of duty before the face of heaven, that an enraged populace do not raze these dens of horror over the heads of the blood imbued wretches who inhabit them.”3

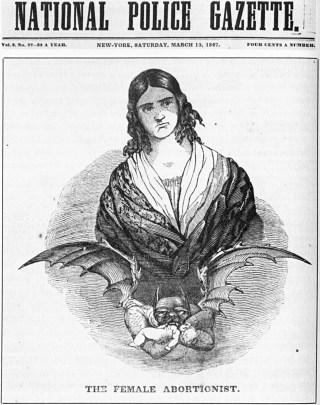

The sensationalist publication even wrote that the bodies of women who died from botched abortions were sold to unscrupulous dissectors: “the carcase [sic] is thrust uncleansed into a sack, lugged to some secret dead-house, and there tumbled out for a medical orgie [sic] and the mutilations of the dissecting knife.”4 Illustrations also supported these words. Historian Carroll Smith-Rosenberg describes one image published in the Gazette referring to Ann Lohmann also known as “Madame Restell,” the most famous abortion provider in nineteenth-century New York City. The illustration depicts a bourgeois woman, “fashionably dressed and attractive,” who is part devil, with her arms turned into demon wings. From the woman’s pelvis comes a “devil’s head with fang teeth gnawing on a plump baby.”5 She-devils and baby killers unite.

Moreover, male “spies” trying to uncover illegal abortion practices are also not new to the abortion debate. U.S. historian Leslie Reagan relates the tale of one early twentieth-century Chicago midwife, Marie Rolick, who warned her fellow midwives of a “state board of health ‘spy,’” who visited her clinic asking for an abortion. The midwife told her colleagues that “‘a male ‘hobble-skirted’ spy with curly, wavy, blond hair,’” was “‘masquerading as a girl,’” to catch her in the act of performing abortions. The spy came to Rolick’s door “‘and offered me [Rolick] $35 to perform an operation and I only laughed. He persisted and … I got angry, grabbed a revolver and threatened to shoot. The ‘girl’ grabbed her dresses around her and she had a pair of trousers on … my suspicions were well founded.’”6

These stories not only make CMP’s current actions look unimaginative in comparison, but also portray them as holding antiquated notions about abortion and women’s rights. Dead babies and spying men reboot.

If tropes of dead babies sold for profits and male spies looking to criminalize abortion are not new, neither is a renewed effort to criminalize abortion. As scholars have argued, we cannot think of abortion in a teleological sense, moving from a criminalized past to an emancipated future.7 Rather, there have been waves of criminalization and decriminalization, periods that often unveil more about shifting notions of gender and women’s roles than about abortion itself. These tales of selling babies remind reproductive justice activists that we must historicize the current moment in order to fight this oncoming tsunami of criminalization.

And in light of the tragic events in Colorado Springs, we must remember that rhetoric is not separate from action. As The Guardian’s Jessica Valenti argued in a recent piece, “Words matter. When we dehumanize people — when we call them demons, monsters, and murderers — we make it easier for others to do them harm. Let’s not pretend that we don’t know that.” No one is safe in this renewed war against abortion rights. And old debates have created new opportunities for anti-abortion activists to continue to do harm.

Further Reading

Manning, Kate. My Notorious Life: A Novel. New York: Scribner, 2013.

Morgan, Lynn M. Icons of Life: A Cultural History of Human Embryos. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

Mohr, James C. Abortion in America: The Origins and Evolution of National Policy. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

Notes

- Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, Rereading Sex: Battles over Sexual Knowledge and Suppression in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Vintage Books, 2002), Chapter 9; Carroll Smith-Rosenberg, Disorderly Conduct: Visions of Gender in Victorian America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 217–244. Return to text.

- Smith-Rosenberg, Disorderly Conduct, 226. Return to text.

- National Police Gazette 1, no. 33 (April 25, 1846): 284. Return to text.

- National Police Gazette 2, no. 27 (March 13, 1847): 212. Return to text.

- Smith-Rosenberg, Disorderly Conduct, 226. Return to text.

- Leslie J. Reagan, When Abortion Was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and the Law in the United States, 1867-1973 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 98–99. Return to text.

- Matthieu de Castelbajac, “Aborto legal: elementos sociohistóricos para o estudo do aborto previsto por lei no Brasil,” Revista de Direito Sanitário 10, no. 3 (2010): 39–72; Reagan, When Abortion Was a Crime. Return to text.

Cassia received her PhD in Latin American History with a Concentration in Gender Studies from the University of California, Los Angeles. Her book manuscript, titled A Miscarriage of Justice: Reproduction, Medicine, and the Law in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (1890-1940), examines reproductive health in relation to legal and medical policy in turn-of-the-century Rio de Janeiro. Cassia’s research has been supported by the Woodrow Wilson Foundation, the Coordinating Council for Women in History, the Fulbright IIE, and the National Science Foundation.