Disability, Responsibility, and the Veteran Pension Paradox

Recently, NPR reporter Quil Lawrence presented a radio series in which he profiled veterans who received other-than-honorable discharges from the military after violating rules of conduct, breaking the law, or getting in trouble with military authorities. Despite their service – including, for many, tours in active warzones – soldiers with so-called ‘bad paper’ are no longer considered veterans. As former Marine Michael Hartnett put it: “You might as well never even enlisted.”[1] Hartnett was given bad paper in 1993 when he began abusing drugs and alcohol – an attempt to self-medicate his undiagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder. Veterans like Hartnett are no longer eligible to receive any of the veterans’ benefits they were promised when they enlisted.[2]

As a historian of veterans, I’ve been following the series pretty closely, and while browsing one of the articles a second time, I was struck by one of the comments. Internet comments, of course, are notorious for being somewhat trollish, but this one resonated. It asked such an old question: where is the sense of personal responsibility from these veterans for their bad actions?

Whether the commenter was aware or not, he or she was pointing at a question that has always been at the heart of the United States’ attitude towards its veterans. How much responsibility does the United States government have to the veterans they create? What must veterans do in order to be deserving of support? Though this was a topic debated by Congress from the time of the Revolution, it came to a head during and after the Civil War. As the numbers of sick and wounded Union soldiers rapidly added up, Congress passed legislation in 1862 that would provide financial support for wounded soldiers by way of disability pensions.

Under this law, Civil War veterans were eligible for a pension if they were disabled during their military service, but actually winning a pension was an exacting process. The Pension Bureau required veterans to see a surgeon to provide a medical certificate. Some men had scars or stumps photographed to provide visual proof of a wound. Most also included affidavits from friends and comrades in their applications to corroborate their disabilities and testify about their character and habits. These positive affidavits often proved crucial: an unofficial, but very real, aspect of securing a pension was successfully navigating the Pension Bureau’s gauntlet of expectations. Veterans had to prove that they were unable to work or were suffering financially because of their disability. In addition, veterans had to establish that they had no “vicious habits” such as drinking, drug abuse, or criminality. Of course, a court martial or evidence of desertion or shirking meant an automatic disqualification.[3]

Many veterans learned the hard way that their bodies and habits were being scrutinized. Abraham Griggs, a Union veteran from New Jersey, received a disability discharge from the Union army in 1863, but when he applied for a pension twenty years later, he was denied. He appealed to his congressman, who tried to push through a private pension bill designed to override the denial – a common practice after the Civil War. Unfortunately for Griggs, President Grover Cleveland chose to review his case before signing the bill into law.

During his first term in office, Cleveland campaigned against the fraud he believed was rampant in the pension system. When he found a pension bill he didn’t like, he gave it a veto, along with an explanation of his decision. When Cleveland examined Griggs’ records, he found that before the soldier’s discharge in 1863, surgeons had noted that they did not “believe [Griggs] sick, or that he has been sick, but completely worthless.” Unfortunately for Griggs, they didn’t stop there. The surgeons went on: “He is obese, and a malingerer to such an extent that he is almost imbecile – worthlessness, obesity, and imbecility, and laziness.”[4] Cleveland vetoed the bill, writing that the veteran’s recent medical examinations revealed no physical signs of disability. He was sure to point out that the most recent surgeon’s certificate stated that Griggs’ “hands are hard and indicate an ability to work.”[5] Even though he had a disability discharge and evidence from witnesses, Griggs had failed to live up to expectations of proper masculine and military behavior, and worse, he claimed disability while he appeared healthy and strong. To Cleveland’s mind, no such veteran was worthy of government support.

It wasn’t just the President who paid close attention to the conduct of soldiers and veterans. Their behavior was under constant scrutiny from the American public. Poor Abraham Griggs had the details of his veto published in a Harper’s Weekly article, which praised Cleveland and condemned Griggs. Although some corrupt Americans might decry the President’s actions, the article stated, “intelligent citizens do not object to such conscientious regard for public duty.”[6] Cleveland wasn’t shaming former Union soldiers – he was protecting the tax-paying public from lazy, mooching cowards.

This preoccupation with veterans’ behavior didn’t end after the Civil War. While World War II veterans were popularly hailed for returning enthusiastically to families and the workplace, Veteran’s Administration psychiatrists were overwhelmed by thousands of traumatized former soldiers. Michael W. Phillips’ recent project for the Wall Street Journal, The Lobotomy Files, reveals the lengths to which the VA went to return mentally ill veterans to a kind of normalcy in the conformist-minded 1950s.[7] Conversely, veterans of the war in Vietnam received intense public scrutiny for their apparent failure to cope with the stresses of warfare and their difficult transition back into civilian life. They were commonly portrayed as bitter, drunk, and crazy — in other words, variations on Forrest Gump’s Lieutenant Dan. Afraid of being associated with this stereotype, many Vietnam veterans avoided seeking treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder until the struggles of Iraq’s and Afghanistan’s veterans brought the issue to the fore.[8]

Even The Daily Show recognized the convoluted nature of veterans’ benefits. On an episode from January 21, Jason Jones tried to make sense of the consequences of other-than-honorable discharges, sarcastically noting, “I think there’s a military term for that.”[9] His joke works because of its accuracy: it’s a Catch-22. Veterans got post-traumatic stress disorder from their military service, which caused them to turn to alcohol and drugs, or to exhibit violent and disruptive behavior, which in turn earned them a less-than-honorable discharge, and so they are denied Veteran’s Administration benefits for soldiers with post-traumatic stress disorder. Civil War veterans faced a similar situation. Even as Northern society praised its veterans for their part in a Union victory, they required them to fit their expectations of a citizen-soldier. If a man reacted to the horror of war by attempting to run from the field of battle, he was a coward and denied a pension. If a veteran turned to alcohol in response to mental trauma, he had “vicious habits” and was denied a pension. If he could not work because his body was damaged or worn out from the hardships of war, he had to try to find work – or at least attest that he wished he could work – or he was denied a pension. To answer the commenter’s question, then, it seems that the veteran’s responsibility was, and is, to meet incredibly high expectations of behavior.

It’s nothing new that as a society we hold our veterans to an impossible standard, but that doesn’t make it any less heartbreaking. Perhaps if we choose to wage war and send our young men and women into its maw, we should be prepared to face the consequences – all of them.

Further Reading

Notes

- [1] Marisa Penaloza and Quil Lawrence, “Path to Reclaiming Identity Steep for Vets with ‘Bad Paper.’”

- [2] Marisa Penaloza and Quil Lawrence, “Other-Than-Honorable Discharge Burden Like a Scarlet Letter.”

- [3] Theda Skocpol, Protecting Soldiers and Mothers: The Political Origins of Social Policy in the United States (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1992).

- [4] Grover Cleveland, “A Veto of the Bill Granting Dependent Pension to Abraham P. Griggs,” February 4, 1887, in The Public Papers of Grover Cleveland, March 4, 1885 to March 4, 1889 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1889).

- [5] Index to the Reports of the Committees of the House of Representatives for the First Session of the Forty-Ninth Congress, 1885-86 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1886), 109.

- [6] “The Pension Raids,” Harper’s Weekly, February 19, 1887.

- [7] See Michael M. Phillips’ project.

- [8] Alan Zarembo, “Vietnam Veterans’ New Battle: Getting Disability Compensation.”

- [9] “PTSD & Vietnam,” The Daily Show, January 21, 2014.

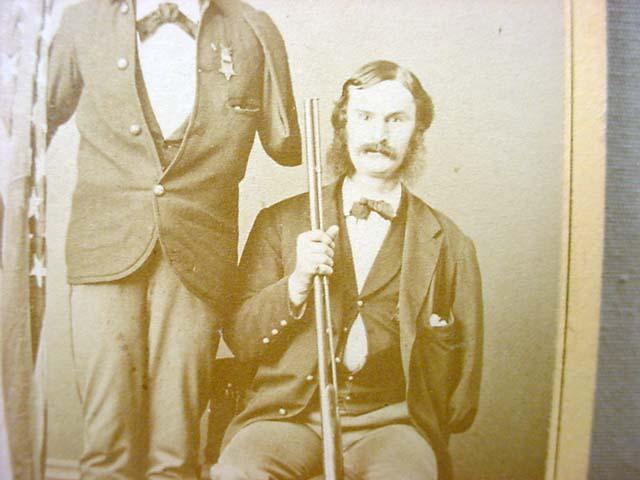

Featured image caption: Civil War, Kelham Hall. (Flickr)

Sarah Handley-Cousins is an Assistant Teaching Professor at the University at Buffalo. She is author of Bodies in Blue: Disability in the Civil War North (UGA, 2019) and a producer of Dig: A History Podcast.

6 thoughts on “Disability, Responsibility, and the Veteran Pension Paradox”

Comments are closed.

What an insightful commentary! It seems to me that we force our damaged veterans to take responsibility for their service, but give our government dispensation.

That is sad the way our country treats our veterans. we need to do a better job helping our veterans after they come back from war. As a country we should all be embarrassed , and ashamed to call are self’s Americans. Thanks you for sharing this . Through knowledge we can change things, without knowledge we can do nothing.

Thank you, Sarah Handley-Cousins, for a succinct and valuable commentary. On the issue of Civil War veterans pensions, is it true that soldiers who fought for the Confederacy were not eligible for pension benefits? I remember reading this somewhere recently, perhaps in Drew Gilpin Faust’s recent book, The Republic of Suffering.

What an excellent, insightful, and thoughtfully written essay. I would be curious to know whether the same strong judgements and biases that are directed toward veterans by the VA & government are also pervasive in the attitudes of VA charities. Frankly, I’ve sometimes wondered why veterans’ charities exist, since veterans’ disability benefits are so generous (provided you can get them). But if the charities’ intent is to act as a safety net for the veterans who aren’t honorably discharged and can’t get access to the benefits they deserve, then perhaps they aren’t so redundant after all.

Jennifer: Yes, you’re correct, Confederate veterans were not eligible for federal pensions. They did sometimes receive small pensions from individual Southern states or support from private organizations.

[…] months ago, when I submitted my first blog post for Nursing Clio, I included a short section about Civil War veterans who had lost their right to a pension because […]