“She Looks the Abortionist and the Bad Woman”: Sensation, Physiognomy, and Misogyny in Abortion Discourse

In November of 1866, a minor sensation rocked the Albany area following the death of the young widow Elizabeth Dunham, who passed away at her mother’s house on the third of the month under, as the Albany Argus primly noted, “suspicious circumstances.” The Argus’s suspicions quickly proved sound. An inquest performed the next day revealed that the unfortunate Elizabeth had died “from inflammation of the womb and bowels, caused by an abortion produced by Pamelia M. Wager.” As more details came out in the press, Elizabeth’s peculiar and distressing death took the shape of a familiar story: a young widow “of handsome appearance,” known for her “high character for religion and fidelity to virtue,” succumbing to the “stealthy, insidious, and winning character” of a charismatic local Lothario named Edward Martindale. Desperate to conceal or erase the eventual visible result of her entanglement with Edward, Elizabeth turned to “the only refuge in such a calamity — that scourge of unfortunate women known as the female abortionist.” Reporting on the story, the New York Herald commented that Pamelia Wager “answers to the description of all such personages — of a stout form, an intelligent but, to the close observer, a sinister countenance. She looks,” the Herald concluded, “the abortionist and the bad woman.”

What a thing to say!

The idea of an easily recognized abortionist is foreign to the contemporary debate over abortion. Today, opponents of abortion fix their concern on organizations like Planned Parenthood, but in the nineteenth century, the abortionist was a familiar villain to newspaper readers throughout the country, and New York state had a particularly sensational lineup. In New York City, the notorious Madame Restell, the Fifth Avenue abortionist, operated a thriving practice, scarcely discouraged by frequent arrests from 1841 on. Her widely published advertisements, along with her regular appearance in the National Police Gazette, made Madame Restell a household name in the nineteenth century, practically synonymous with abortion. In the Albany area alone, local women were familiar with the names of Rachel Bartell, Emma Burleigh, and Pamelia Wager in connection with the “nefarious practice.” Caught at midcentury between the death of the “Beautiful Cigar Girl” Mary Rogers in 1841 and the Great Trunk Mystery of 1871, readers of the Argus found themselves in 1866 taking part in a quintessentially nineteenth-century news sensation, centered on the death of a beautiful, promising young woman at the hands of a sinister, usually female, abortionist. Recognizing readers’ familiarity with the characters in the drama, the Herald held up Pamelia Wager as representative of a type: the image, by her countenance and build, of “the abortionist and the bad woman.”

What should we make of this reporter’s confident assertion that abortionists might be identified by appearance — that Pamelia’s practice could be read in her face along with a more general picture of moral and gender transgression? The Herald’s focus on Pamelia’s physical appearance certainly speaks to the pervasive influence of phrenological thinking in American culture at the time. The notion, promoted by the research of Franz Joseph Gall and his colleagues in prisons across the nation, that character (and, in particular, criminal character) could be read through the visual signs of skull shape, had taken root in Americans’ minds by 1867. Phrenological readings given by practitioners such as the Fowler brothers of New York State had become almost a form of popular entertainment for many middle-class Americans, who absorbed phrenological principles into their moral philosophy. Closely related to phrenology was the pseudoscientific notion of physiognomy, which attempted to locate character not in the lumps and bumps of the skull but in facial features.

In a rapidly industrializing nation increasingly paranoid about the mysterious threat of urban crime, being able to walk down the street and pick out the criminal from the sea of unfamiliar faces proved extremely powerful in the popular imagination. The Herald’s assertion tapped into twin wells of anxiety plaguing respectable America at the height of the nineteenth century. Cities, it seemed, were degenerating into sticky webs of violent crime and sexual lunacy. By midcentury, however, physicians had identified a particularly shocking wave of crime in the very Protestant homes that were supposed to be a refuge against the rise of worldly vices: abortion, a crime, in the words of leading anti-abortion crusader Horatio Storer, “against life … against the mother … against nature and all natural instinct, and against public interests and morality.”1 An abortionist, a woman already unsexed by the disastrously unfeminine practice of medicine who compounded this crime against her sex with the murder of innocence, represented a serious social threat. Yet physiognomy presented reassurance: her features might themselves be a form of natural policing, identifying her by sight as in every sense a “bad woman.”

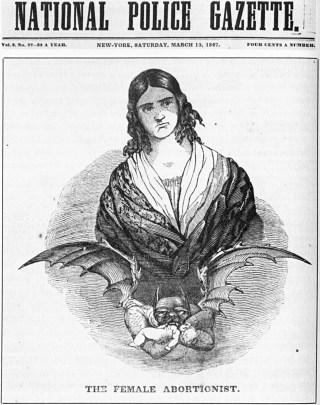

The villains of the anti-abortion narrative constructed in New York’s penny press around the middle of the nineteenth century existed, like so many villains, not just to thrill readers but to enforce a social lesson. Those women who performed abortions were bad women; female criminals whose particular crime represented a unique violation of the caring, maternal role assumed to be essential to womanhood. The longstanding associations lurking in Western culture between witchcraft and midwifery took new form in the nineteenth century in the character of the female abortionist, the ultimate embodiment of crime against sex and against morality. It is no accident that the Police Gazette printed a picture of Madame Restell in the character of a witch, the epitome of a “bad woman,” nor that the Herald emphasized Wager’s physical appearance. Playing this image against that of the pure, innocent, intensely feminine victim, the popular press made misogyny a central component of public discourse about abortion.

It’s interesting to note that these characters — the victimized woman as well as the bad woman — have in large part disappeared from abortion discourse today. These days, the focus falls hard on the fetus: what it looks like, what it might or might not experience at any given point, what happens to it in the act of abortion. The public’s eye has shifted from the face of the abortionist to the fingernails and eyelashes of the fetus. Science’s role is no longer to identify the criminal abortionist, but to map out and define the paradoxically elusive process of reproduction. The concern of current anti-abortion advocates rarely centers on the character of the women involved, but on the potential suffering and violation of the fetuses they carry.

Does this mean that today’s conversation about abortion is less misogynistic than that of the mid-nineteenth century? Well, no. If anything, the disappearance of women from the popular abortion narrative represents a far more insidious kind of misogyny — one that disregards women altogether, either as victims or as villains, as illustrations of the wages of sin or the image of sin itself. The disappearance of nineteenth-century characters like Pamelia Wager and beautiful Elizabeth Dunham from popular discussions of abortion may mean that we’ve stopped looking to the skull to know someone’s character, but it doesn’t mean that opposition to abortion no longer goes hand in hand with an attitude that consistently demonizes women’s actions. The persistent myth of the “bad woman” is still very much alive and well in the abortion debate in America, but today she’s condemned not by her face but by the insistent silence imposed on her.

Further Reading

Amy Gilman Srebnick, The Mysterious Death of Mary Rogers: Sex and Culture in Nineteenth-Century New York (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

A. Cheree Carlson, The Crimes of Womanhood: Defining Femininity in the Court of Law (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009).

Notes

- Horatio Robinson Storer, Why Not? A Book for Every Woman (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1866), 15. Return to text.

“Abortion Case,” Albany Daily Argus (Albany, NY), November 20, 1866.

“Abortion Case at Troy,” New York Herald (New York, NY), November 20, 1866.

Horatio Robinson Storer, Why Not? A Book for Every Woman (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1866).

R.E. Fulton earned a master's degree in American History at the University of Rochester in 2015. Their master's thesis dealt with popular texts on abortion written by physicians in the mid-19th century, and previous research has focused on science fiction publishing in the mid-twentieth century. A student of medical historians who vowed never to become a historian of science, Fulton is now fascinated by questions surrounding history, medicine, print culture, feminism, and popular science.